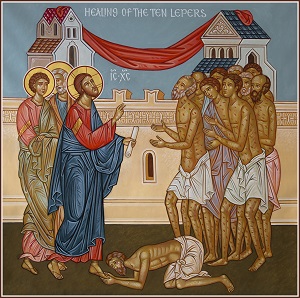

I think

the worst thing we could ever teach someone is that they should keep their

distance from Jesus. Yet, this is what

these ten lepers were taught. Not specifically

from Jesus, of course, they’d been taught to keep their distance from everyone

who didn’t share their disease. When the

first signs of leprosy were noticed on someone’s skin, there would be a funeral

style liturgy in which the victim would be mourned as if dead when cast out of

the community, shunned, told to remain perpetually separate, to cry out to warn

people not to come near them. They were

taught that their skin was so dreadful, literally, something that people

dreaded so, that they must keep away, because they were dangerous, because they

were to be feared. They were taught to

hate their own skin, taught that the only useful thing they could do with their

lives was to help others avoid them.

So, when

Jesus even talks with them, even lets his gaze rest upon them, he’s disrupting

a pattern. He’s doing something risky on

the basis of much ancient medicine, letting his eyes be imprinted with disease,

which could harm him. There’s no reason

to think that Jesus didn’t think of this as risky; there’s every reason to be

sure that he never lets risk keep him from loving someone. So, he looks, he talks, and he directs them

to go to the priests. In both Israel and

Samaria, the priests functioned as kind of ‘purity inspectors.’ They made no claims to be able to cure

leprosy, but they could diagnose it, and functioned as gate-keepers for who got

included and who got shunned, deciding whose skin was to be feared.

And all

ten of the lepers have enough faith to go, despite the fact that the text tells

us that none of them were cured at the point when they turn around and start

going to their respective priests (the Samaritan the most daring, as he goes

alone to find a Samaritan priest). They

go, prepared to be laughed at, derided, chased out of town, failing in their

one mission to help others avoid them, exposing again their dreaded skin to

authoritative inspection. Their willing

obedience to Jesus’ word is witness and challenge enough to us. As Paul says,

there’s power in Jesus’ word. It’s not chained, and neither are these lepers once

they’ve heard it.

One, the

Samaritan realizes that he’s been healed. He’s the only one we hear that of. The other nine have drunk so deeply of the toxic

Kool-Aid that they’ve internalized the message behind their shunning: that

their skin is dreadful, they’re dangerous, they’re to be feared. We can’t see what we don’t consider possible,

and their sense of the possible has been so assaulted that they can’t conceive

of their bodies as having dignity, they can’t notice they’ve been cured. But, somehow, the Samaritan can. That original spark of divine brilliance so

dimmed and defiled has not been extinguished.

Despite all the marginalization, this one notices. He’s been healed. Not just cured, it’s not just that his

symptoms have been taken away, he’s been healed, he’s been restored to

wholeness, a wholeness that allows him to express the fullness of his dignity

in the highest human act going: giving thanks to God. Augustine would talk about learning to say

thank you as they fundamental task of discipleship. There’s power in Jesus’

word. It’s not chained. It forms this man for thanksgiving.

Here in

this Eucharist, we are formed for thanksgiving. That’s what the word Eucharist

means in Greek, thanksgiving. For Christ’s word is proclaimed here, and Christ’s

word has power, it is not chained. Here in this Eucharist, we become more aware

of what we need to be healed of, we become more away of our brokenness and of our

sin. But that shouldn’t train us to hide ourselves, to help others avoid us,

but Christ is rewriting that script. Here, the crucifix is carried through our

midst. Here, Jesus Christ, body, blood, soul and divinity, is present under

form of bread and wine, and doesn’t keep his distance but comes even closer, so

much closer, to us than he did to those lepers. For many of us he comes through

reception of the Eucharist. Eating. Drinking. For all of us he comes through

the word, the unchained word, and the privilege of watching his body break for

us.

And that

message, that no-one’s aim in life is to help other people avoid them, matters.

Because we still teach people that. Jesus still has a script to flip. We may

but shun literal lepers, but we still make people feel feared because of what

their skin looks like. We are part of a

society that tells young black men, especially those with strong-looking

bodies, that people are scared of them, and they should do whatever is

necessary to avoid that, to be less dreaded, because that’s the only way for

them to stay safe. Our society has said the same thing to people who are HIV+,

by so cultivating an irrational fear of their bodies that the Fair Housing Act

had to be re-written so that they could participate fairly in that market. Our

society weaponizes fear to shun and marginalize.

Have we

not learned from Lazarus and the rich man?

That when we inscribe chasms in our world, God may well respect those,

but we can’t expect Him to put heaven on our side of the chasm? Our world is so in need of healing. And all this fear touches our hearts too. We are in so much need of healing. And Jesus has so much to give. His word has

power; it is not chained. It will form of us for a life of eternal

thanksgiving.

No comments:

Post a Comment